The Sci-fi Creators Who Made Expo ’70 (1/2)

How Japanese SF Shaped Asia’s First World’s Fair

From the outset, the modern world’s fair, or world expo, has invariably offered hints of possible futures. The first—Britain’s Great Exhibition of 1851—showcased the flush toilet and a precursor to the fax machine, while world’s fairs that followed in Paris (1855), Vienna (1873), and elsewhere introduced humankind to such marvels as the lawn mower, the washing machine, and the electric telegraph. Through exposure to the latest prototypes and gizmos, visitors caught hazy glimpses of the social transformation technology was destined to bring.

It was not until around the late 1930s, however, that world’s fairs did more than merely gesture to the future through newfangled gadgetry and began to offer explicit visions of what might come. Their official slogans or “themes” illustrate this transition, which, not coincidentally, overlaps perfectly with the Golden Age of science fiction (1938-early 1960s):

“Building the World of Tomorrow”

(1939: New York World’s Fair)1“A World View: A New Humanism”

(1958: Brussels World’s Fair)“Man in the Space Age”

(1962: Century 21 Exposition, Seattle)“

The influence of science fiction on a world’s fair was nowhere more direct and significant, perhaps, than in the case of The Japan World Exposition, Osaka, 1970. 2

Science Fiction and Expo ‘70

Although Japanese science fiction dates back at least to the 1857 story A Feel Good Tale of Conquering the West, nearly a century would pass before it developed into a distinct genre. Traces of SF could be found in such storytelling movements as the utopian fiction of the late 1800s, the adventure tales of the early 1900s, and the detective fiction of the 1920s and 1930s, but they never managed to coalesce.

By the time the Japan World Exposition convened in Osaka in 1970, however, sci-fi was not just fully formed; it was a multimedia pop cultural and countercultural phenomenon. The sci-fi novel and short story form had matured, modern anime and manga had been born, the kaiju giant monster and tokusatsu hero film genres had already spawned multiple franchises, organized fandom was burgeoning, and professional creators had found community in the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writer’s of Japan.

Given the degree to which the SF industry was booming in the lead up to Expo ’70, is it any wonder that the fair’s organizers would ask a legion of sci-fi creators to assist in its conception and design?3

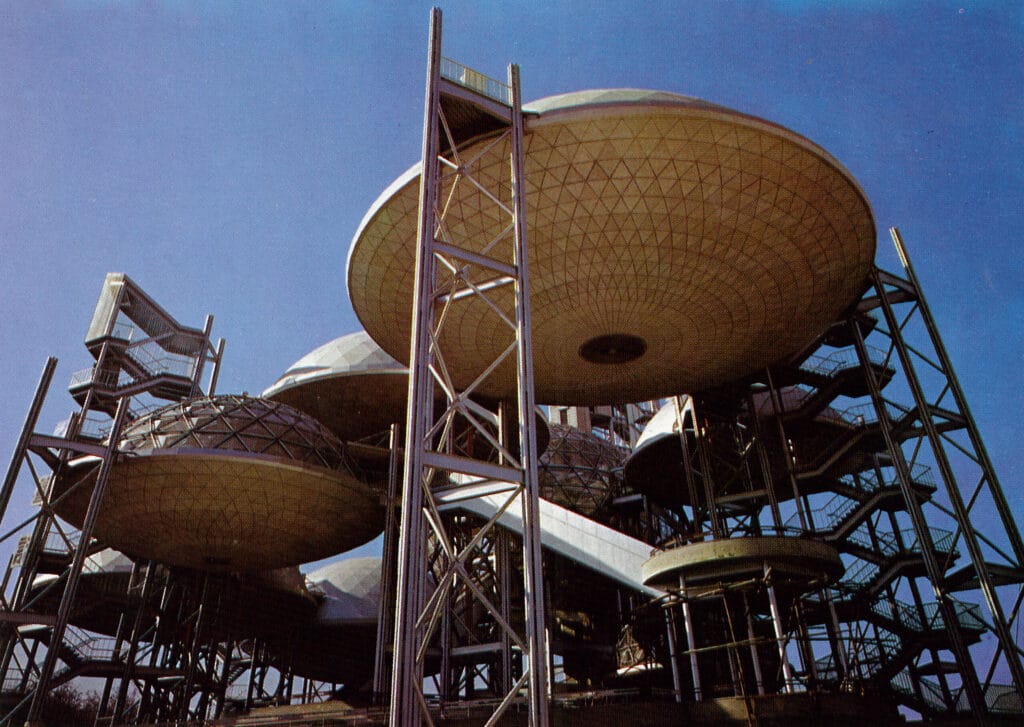

Expo ’70 was the first world’s fair in Asia. During the six months it was held between March and September, the event attracted a record of over 64 million visitors, with participants from 78 countries. Over a dozen architects were employed in designing the site, which the press frequently described as a “city of the future.” Raised moving walkways connected the Symbol Zone that served as the central hub of the exposition site to the corporate pavilions to the east and the national pavilions to the west.

It was hard to be more futuristic than moving walkways in 1970, but Expo ‘70 certainly tried. There were the giant robots Deme and Deku who made appearances in the Festival Plaza. There was the time capsule in the Matushita (i.e. Panasonic) Pavilion, set to be sealed for 5,000 years; the human washing machine or ultrasonic bath pod in the Sanyo Pavillion; the flight simulator in the Hitachi Pavillion; a moon landing simulator in the IBM pavilion; and an early wireless telephone in the Electronics and Communications Pavilion; not to mention the radically new architecture of the Metabolist movement.

Komatsu Sakyo and Expo ‘70

It was primarily in the Symbol Zone and corporate pavilions where sci-fi creators left their mark. The most important was Sakyo Komatsu (1931-2011). In 1970, he was a prominent though not yet wildly successful novelist, but in just a few short years he would be propelled to fame by Japan Sinks (1973). The novel, imagining a disaster in which the Japanese archipelago sinks beneath the Pacific Ocean, would win the Seiun and be immediately adapted into manga, film, and TV drama forms, eventually selling 4.6 million copies. Komatsu would also come to be numbered among the Three Masters of sci-fi—along with flash fiction wizard Shinichi Hoshi (1926-1997) and prolific experimentalist Yasutaka Tsutsui (1934-present)—all of whom both assisted and critiqued the expo in different capacities.

Komatsu’s involvement began in 1964 when he helped form Thinking the Expo, a research group dedicated to studying the coming Japan expo. The group was motivated by pure academic interest, but was later coopted by the government. It would then take a leading role in developing the expo’s core ideas, including the theme Progress for Humanity and Mankind. Komatsu contributed intensively at every step and was ultimately hired directly by avant-garde artist Taro Okamoto (1911-1996), who would design and produce the Theme Pavilion, along with the enduring symbol of Expo ‘70, The Tower of the Sun.

Komatsu was named a sub-producer for the design team that would translate the theme and sub themes he had helped theorize into palpable exhibits. Ironically, given that Komatsu was a sci-fi author who had recently helped to inaugurate the field of future studies in Japan, he was put in charge of “Past: The World of Origins.” Located in the underground of the Theme Pavilion, the exhibit depicted the emergence of life in stages from atoms to simple molecules, to nucleotides and RNA/DNA before culminating with the individual human and human society, covering a vast timescale on the order of Komatsu’s Arthur C. Clarke inspired novel The End of the Endless Flow (1966).4 In the words of Shinichi Hoshi commenting on the exhibit for SF Magazine with characteristic wry wit :

It taught me very clearly how life emerged in stages from the primordial chaos of the universe and evolved at last into the dumb and pathetic creature we call the human being.

A Who’s Who of the Sci-fi World

The other sci-fi creators who made Expo ‘70, in large part due to Komatsu’s involvement, constituted a who’s who of sci-fi in 1970.

Design of the Mitsubushi Future Pavilion was overseen by Godzilla producer Tomoyuki Tanaka (1910-1997). He was assisted by Shinichi Hoshi, novelist and Dune translator Yano Tetsu (1923-2004), SF Magazine editor-in-chief Masami Fukushima (1929-1976), and futurist illustrator Hiroshi Manabe (1932-2000), with music by Godzilla-roar composer Akira Ifukube (1914-2006). The pavilion imagined the future development of all domains of the planet, from sea to earth to sky, with displays of an underwater city and power plant, space stations, and an atmospheric station for controlling the weather. There was also a video on the birth of the Japanese islands, a sort of reverse Japan Sinks, created by Ultramanspecial effects pioneer Eiji Tsuburaya (1901-1970), one of his final works before his death.

The Fujipan Robot Pavilion was produced by Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), the father of modern manga and of the first anime in the form of robot boy series Astroboy. He was assisted by Aritsune Toyota (1938-2023) a novelist and screenwriter who cut his teeth on Astroboy scripts and who would later help create the landmark anime Space Battleship Yamato. Together, they produced the Robot Forest, where visitors could mingle with robots who sang, danced, performed music, juggled and played. In a jocular report for the Weekly Sankei paper, Yasutaka Tsutsui writes:

“The rock-paper-scissors robot wields a hammer, which he uses to bash you on the noggin if you lose a round to him. He got me too, the bastard. […] The robot working reception is astonishingly beautiful, with a mouth that moves just like a person’s. Which is to say, this gal’s an android. I noticed that part of her lipstick had been rubbed off. Seems that some so-called adults try the most outrageous things.”5

The Auto Pavilion included the farcical sci-fi film 240 Hour Day, screenplay by Kobo Abe (1924-1993), author of arguably the first modern Japanese sci-fi novel Inter Ice Age Four (1958) and one of Japan’s most renowned literary figures.6 Projected on four screens, the half hour short depicts the surreal effects of a neural accelerant called Acceleratine that makes humans an order of magnitude faster, thereby stretching a single day into 240 hours.7

In a representatively absurd boxing scene found in Abe’s screenplay, a pattern is repeated, with one cornered fighter receiving a puff of Acceleratine from his coach and using his heightened speed to beat his opponent into the corner, only to be beaten back again when his opponent receives his own dose. In this way, the fighters take turns pulverizing each other at increasingly higher doses and speeds until:

The motion of the fighters is now almost too fast to see. Just as the overwhelmed referee calls to someone outside the ring to ask for his own dose of Acceleratine, the limbs, heads and other parts of the two fighters warp, stretch, and tangle before ripping off and and flying in all directions.

A huge cheer erupts from the crowd.

The referee lifts up pieces of an arm and a leg and declares a draw. The indignant crowd begins to hurls things into the ring; some pluck off and throw their own limbs.

Critical Voices

The involvement of all these creators in Expo ‘70 was an early example of what might now be called futurist consulting, design fiction, or SF prototyping. It was a sign of just how much credibility the nascent science fiction industry had earned despite its reputation as something puerile and aberrant throughout the 1960s.

The decision of the creators to be involved in the fair, however, was not without political import. As with many world expos throughout history, the event was mired in controversy.

In part two of the Sci-fi Creators Who Made Osaka Expo ’70, I’ll look at the protest movement surrounding the fair, and the ways in which sci-fi creators either reinforced or cut against it.

1 The 1939 New York World’s Fair, which marks a shift for world’s fairs towards explicit futurism, coincided with the 1st World Science Fiction Convention, held in Manhattan July 2-4 of that year.

2 For firsthand reportage on Expo ’70, read this two part article by Japan journalist OG Mark Schreiber: Part 1 and Part 2

3 In writing this essay, I relied upon numerous sources but am especially grateful for the work of sci-fi historian Yasuo Nagayama and Japan scholar William O. Gardner.

4 As noted by Gardner.

5 Many of the robots from the robot forest have been preserved and are now on display at the Aichi Children’s Center, as detailed in this article (Japanese only).

6 The film was directed by Abe’s frequent cinematic collaborator Hiroshi Teshigahara, who I have relegated to a footnote despite being one of Japan’s most acclaimed director’s because he has little to do with sci-fi history.

7 The film was thought lost for decades but was recently discovered and digitized. It is now occasionally screened at theatres in Japan. I, for one, am dying to see it.

About The Author

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle (Skyhorse), a trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo, and a translator of Japanese literature, including most recently the bestselling memoir The Traveling Tree (Hachette) by renowned photographer Michio Hoshino. He also writes in the Japanese language, serving as a story consultant for a well-known video game company, and contributing short stories to such publications as a 2025 anthology put out by Japan’s largest sci-fi publisher. His translations, essays, and works of fiction have appeared in Granta, Aeon, Monkey, and more.

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle (Skyhorse), a trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo, and a translator of Japanese literature, including most recently the bestselling memoir The Traveling Tree (Hachette) by renowned photographer Michio Hoshino. He also writes in the Japanese language, serving as a story consultant for a well-known video game company, and contributing short stories to such publications as a 2025 anthology put out by Japan’s largest sci-fi publisher. His translations, essays, and works of fiction have appeared in Granta, Aeon, Monkey, and more.

Read Eli’s full bio.