The Sci-fi Creators Who Made Osaka Expo ’70 (2/2)

How Japanese SF Critiqued Asia’s First World’s Fair

Judging by its marketing copy, Expo 2025, currently being held in Osaka, seems desperate to be seen as heralding the era to come. The word “future” is used almost compulsively, not only in the theme Designing Future Society for Our Lives, but in names for pavilions and official exhibitions such as “Future City”, “Future Society Showcase”, and “Marketplace of the Future.” Apparently having a “Future Life Village” is not enough; there must also be a “Future of Life” pavilion. It is as if the organizers want us to believe that the world’s fair is itself a kind of prophecy, a grand work of divination in the form of transient architecture, displays, advertisement, and merchandise.

Such easy and hubristic claims to clairvoyance so permeate nearly every avenue of human enterprise in our terminal capitalist era that we hardly notice them anymore. This marriage of futurism and industry was not, however, always so commonplace. Although world’s fairs have consistently gestured to the future to some degree since their birth in the 19th century, there was a time within living memory when explicit reliance on the speculative imagination was something fresh, even controversial.

The turning point came with The Japan World Exposition, Osaka, 1970, whose organizers relied upon the toolkit of science fiction to an unprecedented—and as still unmatched—degree. As I documented in part one of this two part article, a who’s who of sci-fi creators, centring around novelist Sakyo Komatsu, helped develop the core concepts and design the exhibits. From manga and anime originator Osamu Tezuka to tokusatsu pioneer Eiji Tsuburaya and absurdist literary heavyweight Kobo Abe, just about every figure that was integral to the formation of modern Japanese sci-fi contributed to Expo ‘70.

Their involvement was an early example of what might now be called futurist consulting, design fiction, or SF prototyping. It was a sign of just how much credibility the nascent science fiction industry had earned despite its reputation as something puerile and aberrant throughout the 1960s.

Yet the decision of these many creators to lend their creative energy to the fair was not without political import. As with many world expos throughout history, the event was mired in controversy.1

Expo ‘70 and The Anpo Protests

In a 1966 essay, just two years after release of his debut novel The Japanese Apache, Sakyo Komatsu describes his ideal of what a world’s fair ought to be:

For us, the goal is not to create some grand international recreational diversion called the World Exposition. On a planet where we continue to struggle with disharmony, imbalance, and opposing contradictions as a result of numerous misunderstandings even as we develop remarkable technologies and civilizations, our true aim is to attempt to create an Expo as a global space for the exchange of wisdom and information, in order to discover measures that can promote the happiness of all of humankind and of the entire world in its boundlessly diverse constitution while resolving inconsistencies.

From such highfalutin optimism would emerge the theme of Expo ‘70, Progress and Harmony for Mankind, developed by Komatsu and other members of his Thinking The Expo research group. Clearly the intention was to inspire. But to many Japanese in the years leading to 1970—amid overpopulation, ever-worsening pollution, and deepening wealth inequality—it sounded like a bad joke. Critics of the fair charged it with ignoring critical issues in the name of an empty and dangerous nationalism.

There is no doubt that Expo ‘70 was in part intended to project an image of national strength. With its moving walkways, encircling monorails, robotics, portable phones, flight simulators, human washing machines, ubiquitous video displays, and regular announcements that the energy for all of this was provided by a nearby nuclear power plant, the fair was an opportunity for Japan to demonstrate its technological and scientific capabilities.

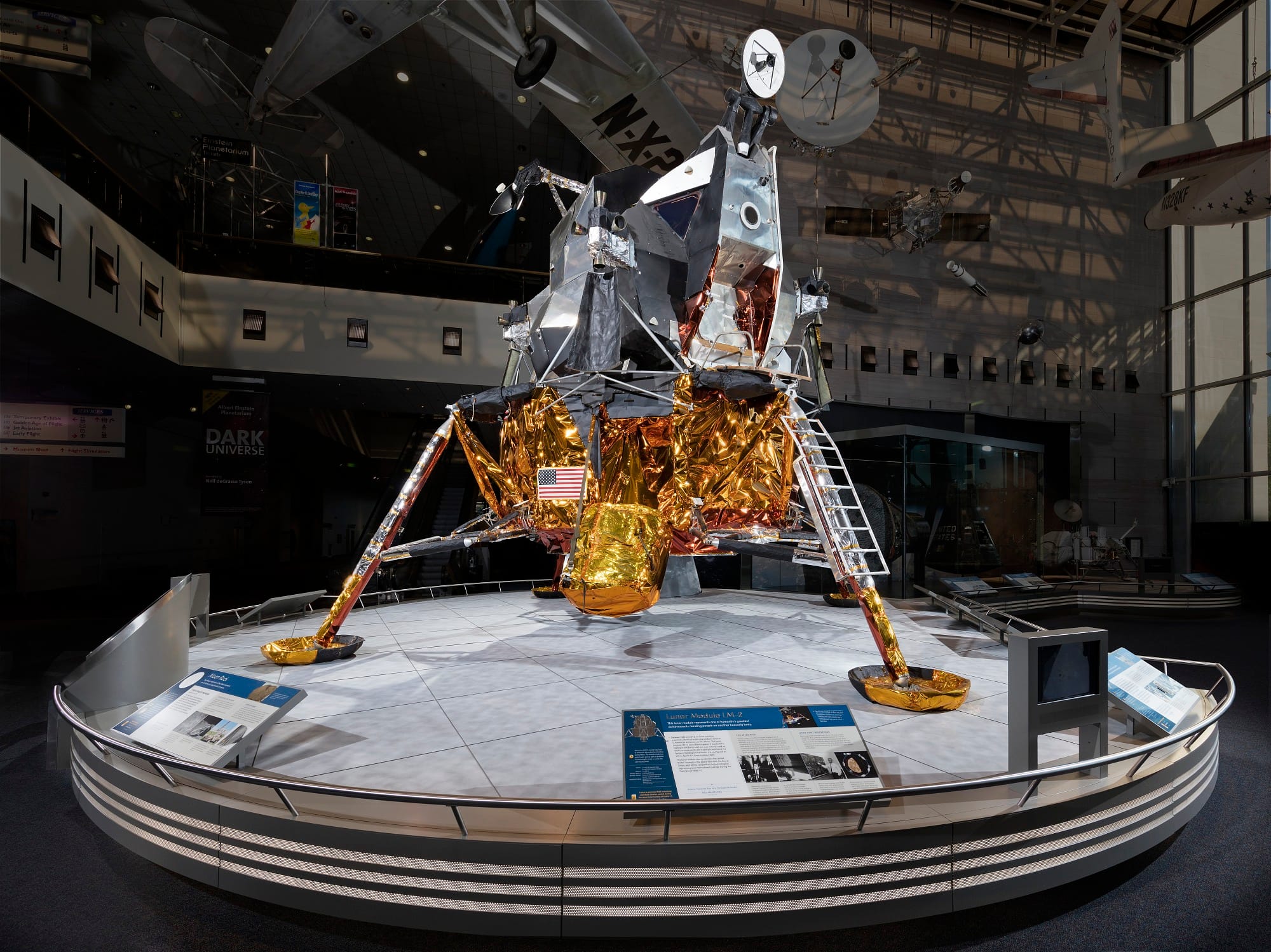

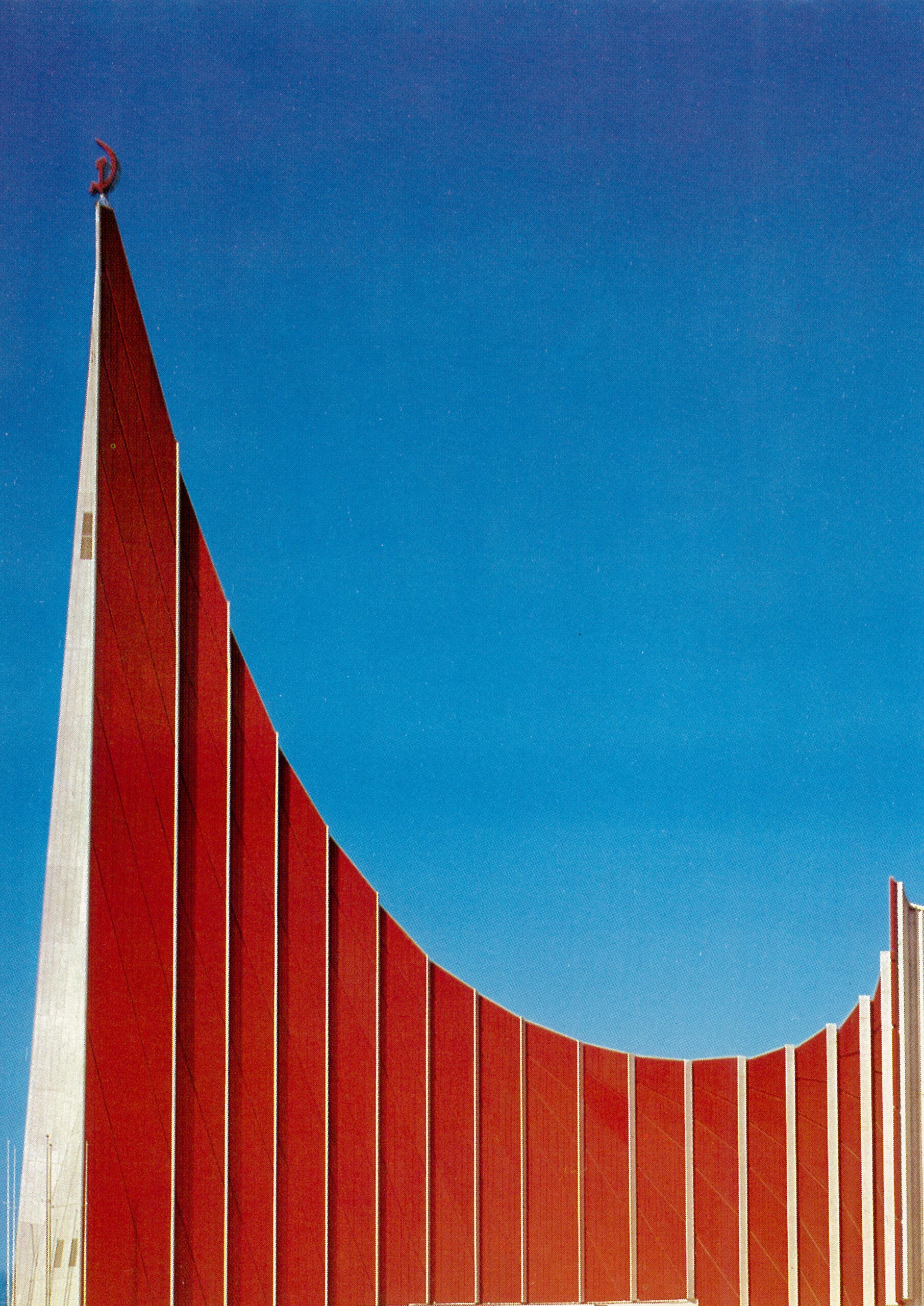

Other nations were just as eager to show off. With the first landing on the moon from the previous year still fresh in global consciousness, the two Cold War superpowers used Expo’ 70 to trumpet their relative progress in the nascent Space Age. The Soviet and American pavilions ended up being the two most visited of all the national pavilions, with a moon rock collected by the Apollo 12 astronauts vying for attention with a life-size model of a Soyuz-4 alongside other spacecraft.

Projections of nationalism by the Japanese government were especially suspect to the citizenry due to the controversy surrounding the US-Japan Security Treaty—also known as Anpo—which allowed American military bases to operate on Japanese soil. When Anpo was revised in 1960, it ignited the fiercest protests post-defeat Japan has ever seen, with hundreds of thousands surrounding the National Diet and an estimated 30 million participating in protest actions across the nation. With the treaty up for renewal in 1970, the movement was revived, if at smaller scale, and Expo ‘70 became symbolic for many of all that was wrong with so-called “progress” in the archipelago.

Bubbling up from the Anpo movement were anti-expo resistance groups. Many were formed by artists who carried out protest actions known in the parlance of the day as “happenings.” Two of the most famous happenings involved the Tower of the Sun, the architectural centrepiece for the entire expo grounds. The first was when avant-garde dadaist artist Kanji Itoi (aka Dadakan) ran naked beneath the tower; the second when antiwar activist Hideo Sato seized one of the eye sockets of its Golden Mask, initiating an eight day hunger strike in what was described as an “eye-jacking.”

One prominent critic of the fair was Kenzaburo Oe, a novelist who would win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1994 and make his own sci-fi contribution just five years earlier with the two novels in his almost universally panned Healing Tower duology. In a rambling polemic, Oe describes the apocalyptic mood in the air in 1970 and complains that Expo ‘70 futurists, presumably Komatsu and his Thinking the Expo colleagues, have produced excessively rosy visions that distort the true nature of the zeitgeist.

I can’t help thinking that there were frequent events in the year 1970 that seem to portend, if saying the end of the world is too much, then at least the end of our nation and the end of us… The world fair happened this year. Supposed experts of the future, not even considering the atmosphere of end times, cooperated like academic guard dogs of the status quo.

Expo ‘70 *in* Science Fiction: Commercialism and Satire

SF creators not only shaped Expo ‘70; they also wrote stories inspired by or set at the fair. Some of these stories tended to reinforce the prevailing order in much the way that Oe complains. Others were more critical, revealing sympathy with the protestors.

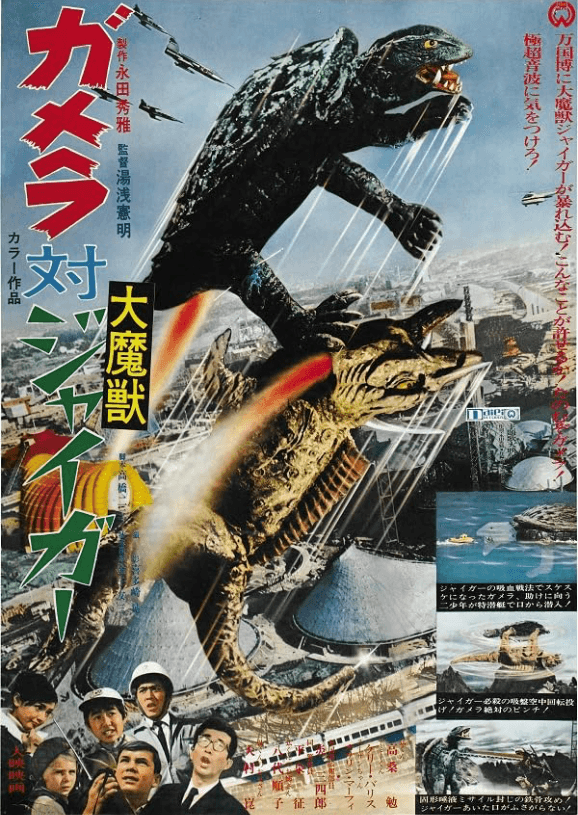

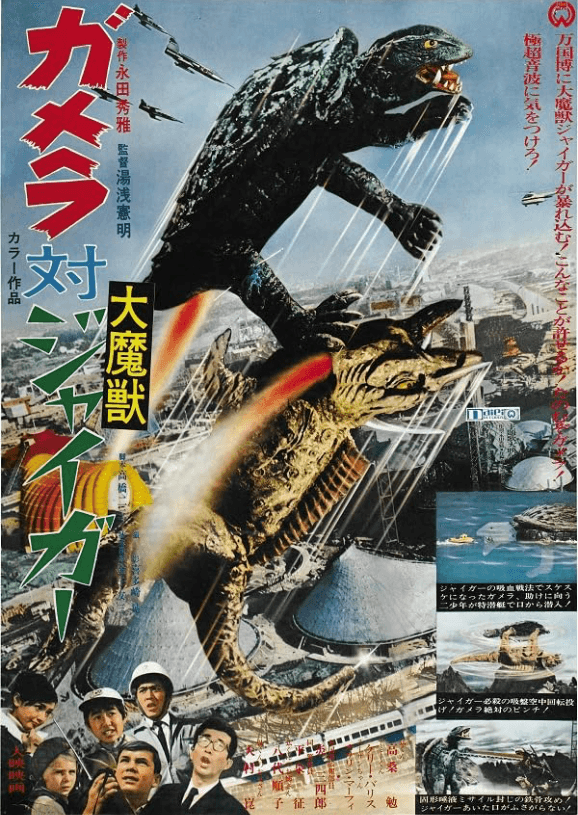

The best example of a story in the former camp is Gamera vs. Jiger. This instalment of the Godzilla-copycat Gamera franchise was not only set partly at Expo ‘70 but was scheduled to screen during the event and had a direct merchandising tie-in.2 The plot of this kaiju B movie (which at time of writing has a 32% and 5.2/10 rating on Rotten Tomatoes and IMDB, respectively) centres around an ancient slumbering monster called Jiger who awakens from his underground lair and attacks Osaka, threatening the success of the Expo.

“Right as we speak, visitors from all over the world are canceling their hotel and flight reservations for the expo,” says an official in the film. “We have to deal with Jiger, or there is no way we can open the expo. And if Jiger destroys the expo site itself, what will we do?”3

As Japan scholar Andrew C. Elliot notes: “Osaka itself may burn, this official seems to suggest, but the expo must be protected.”

Not the Expo!4

Thankfully, such blatant and inane promotion of the fair was offset by several stories that took the political stakes more seriously.

One sci-fi story critical of the fair preceded it by several years: Taku Mayumura’s novel, Expo ‘87, released in 1968 at the height of anticipation for Expo ‘70. It imagines a follow-up 1987 Japan expo around which zaibatsu representing an assortment of speculative industries engage in backroom politicking as they struggle for influence over the fair. Via the mirror of the future, the novel offers oblique commentary on the shady commercial dealings surrounding Expo ‘70.

The most astute and entertaining critical takes of Expo ‘70, however, were undoubtedly those of Yasutaka Tsutsui, a sci-fi provocateur who remains one of history’s most lauded Japanese authors, both within the genre and in the mainstream literary world. In 1970, he wrote not just one but two stories that satirize the fair.

The first was The Expo at Midnight in which a sci-writer (based on Tsutsui himself) is offered a freelance gig writing an article about the expo grounds at night time. The protagonist accepts the job mainly as an excuse to have an affair with a young model, and while riding the bullet train to Osaka with her, reflects on what he thinks of the fair:

They say that expos are the most idiotic undertaking of which humankind is capable and that there are plenty of better things we could put our energy into. But this doesn’t doesn’t seem like a problem to me because I think there’s plenty of value in idiotic undertakings as long as they’re thoroughly idiotic… There’s no way that humankind is going to make progress or become more harmonious just by holding an expo… .

After failing disastrously to woo the model (due to the ludicrously poor hotel room provided by his employer, in which the pair have to share their futon with a group of bed-wetting children), the writer visits Expo ‘70 after nightfall to discover that it is the staging ground for a tangled bout of Cold War espionage. His employer, who is actually a CIA agent in disguise, explains that each of the pavilions operates like an embassy, subject only to the laws of its home country. As a result, USA and USSR agents keep entering the pavilions pretending to be visitors and defecting to the other side. The eventual upshot is a shootout between the KGB, FBI, CIA, and (for some reason) Frank Sinatra’s mafioso family, with an army of garbage collectors, defectors, and night watchmen caught in the crossfire. In the amidst of all this, the flying-saucer-shaped American pavilion turns out to be the real deal and takes flight, entering the fray with flame-thrower blazing.

The Expo at Midnight lampoons the petty symbolic competition for national superiority played out at Expo ‘70 by infusing the fair with elements of actual geopolitics. Another story dropped by Tsutsui in 1970 uses exactly the same technique, firing a second sally against the Progress and Harmony for Mankind theme developed by Tsutsui’s friend Komatsu, this time through a more explicitly speculative concept.

When the protagonist of The Great Disharmony of Mankind enters the fair grounds early one morning, he discovers a thatched hut with a dead child lying outside. A hastily scrawled sign advertises the hut as the My Lai Pavilion. This is a reference to the 1968 My Lai massacre, a war crime perpetrated by the US Army on unarmed Vietnamese civilians. Upon venturing inside, the protagonist finds American soldiers gunning down women, children, and the elderly. When passing expo visitors are hit by stray bullets, the police demolish the hut, only to find it reappearing in different places each morning, whereupon the same bout of mass murder is recapitulated. Soon the Biafra Pavilion, referring to the secessionist state of Biafra that suffered extreme famine during the Nigerian civil war (1967-70), begins to appear each day, disgorging hordes of refugees who swarm the expo restaurants begging for food. When the international community expresses its indignation and appall, the Japanese government decides that the only response to the insult and inconvenience to other nations that the ghost pavilions represent is for Japan to insult and inconvenience itself by setting up its own ghost pavilion: the Nanking Massacre Pavilion!

Sakyo Komatsu Rethinking the Expo

As noted earlier, Komatsu began his involvement in Expo ‘70 with a highly optimistic conception of the ideal expo. However, once he and the other members of Thinking the Expo were coopted by the government, and he shifted from considering world’s fairs in the abstract to helping design an actual fair, his views began to shift. In an autobiographical work written many years later, he expresses regret at being unable to extricate himself from the project due to the aggressive overtures of government officials. Ultimately, Komatsu was disappointed with many aspects of Expo ‘70’s implementation, particularly government censorship of attempts by him and other creators to add nuance to the notion of progress by acknowledging attendant dangers.

The most striking example of how dystopian currents were suppressed is the case of the Wall of Contradictions. This photomontage hung in the Theme Zone was intended to illustrate the dichotomy between peace and war and destruction, especially the horrors of nuclear weaponry. But the government organizers decided at the last minute to censor images of corpses and those left with keloid scars after the bombing of Hiroshima, thereby dehumanizing the imagery and leaving a less impactful display of impersonal urban devastation and mushroom clouds.

Expo ‘70 as a Microcosm of Sci-fi Politics

Komatsu’s ambivalence about his central role in planning and producing Expo ‘70 is emblematic of an ambivalence inherent within the field of science fiction as a whole. At its best, sci-fi helps reorient humankind on its historical journey by generating cognitive estrangement and breaking down the ossified views of reality that hinder us; at its worst, sci-fi reinforces the dominant ideology and lulls us into blind faith in progress through comforting theme park utopias and stale throwback futures. It is the speculative imagination underlying this latter form of critical-faculty-paralyzing sci-fi that the powers that be tend to manipulate and wield for the sake of their own profit and position.

Komatsu and other creators were drawn to the expo for the chance to make a difference (and almost certainly for money and exposure). But their output was distorted by the interests of industry and government. This should stand as a warning to all sci-fi creators—especially those drawn into the sometimes lucrative enterprises of SF prototyping, design fiction, and other flavours of futurist consulting—on how entrenched political and economic forces can stunt and siphon the transformative potential of the art form.

Looking Ahead: The International SF Symposium

Similar political dynamics were on full display at another event organized by Komatsu that was held to coincide with the Expo: namely, The International SF Symposium. In the next instalment of the History of Japanese Science Fiction, I will cover this landmark event. It is a tale of Cold War intrigue, nuclear bomb story wars, and Brian Aldiss’ legendary fully clothed dip in Lake Biwa.

As with part one, I consulted many sources in the writing of this article but am particularly grateful to the work of William O. Gardner and Yasuo Nagayama.

This tradition of commercial tie ins has been perpetuated by the current Osaka Expo with the Gundam franchise: https://www.nippon.com/en/news/p01980/

As translated by Andrew C. Elliott in A Place for Noise: Dissonance, Protest, and Youth in Expo ’70 and its Representations, which includes an extended analysis of Gamera Vs. Jiger.

Decades later, Naoki Urasawa’s bestselling 2006 manga 20th Century Boys heavily features the expo in its nostalgic treatment of the mid Showa era.

About The Author

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle (Skyhorse), a trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo, and a translator of Japanese literature, including most recently the bestselling memoir The Traveling Tree (Hachette) by renowned photographer Michio Hoshino. He also writes in the Japanese language, serving as a story consultant for a well-known video game company, and contributing short stories to such publications as a 2025 anthology put out by Japan’s largest sci-fi publisher. His translations, essays, and works of fiction have appeared in Granta, Aeon, Monkey, and more.

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle (Skyhorse), a trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo, and a translator of Japanese literature, including most recently the bestselling memoir The Traveling Tree (Hachette) by renowned photographer Michio Hoshino. He also writes in the Japanese language, serving as a story consultant for a well-known video game company, and contributing short stories to such publications as a 2025 anthology put out by Japan’s largest sci-fi publisher. His translations, essays, and works of fiction have appeared in Granta, Aeon, Monkey, and more.

Read Eli’s full bio.