Oppenheimer and The Nobel Peace Prize

Thoughts on a film review translation and existential risk

My translation of an essay that adopts the perspective of Nagasaki and Hiroshima survivors to remind us of the danger of nuclear weaponry could not have been published at a more symbolically powerful moment, just hours before the Nobel Peace Prize went to nuclear bomb survivor confederation Nihon Hidankyo.

On Oppenheimer: Christopher Nolan’s Moral Stance by Keiichiro Hirano—whose novels and other writings I frequently translate—is a critical essay that considers the ethical implications of Nolan’s multiple academy award winning film Oppenheimer, in part, through the eyes of nuclear bomb survivors or hibakusha. While I generally maintain a policy of letting my translations speak for themselves, the timing of this translation’s release on the Shinchosha site prior to the Nobel announcement last Friday feels so significant and the political issues involved so urgent that I can’t help putting on my writer’s hat to say a few words.

First, I think the recognition granted to Nihon Hidankyo is well-deserved. In the words of the Norwegian Nobel Committee in their press release:

This grassroots movement of atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, also known as Hibakusha, is receiving the Peace Prize for its efforts to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons and for demonstrating through witness testimony that nuclear weapons must never be used again.

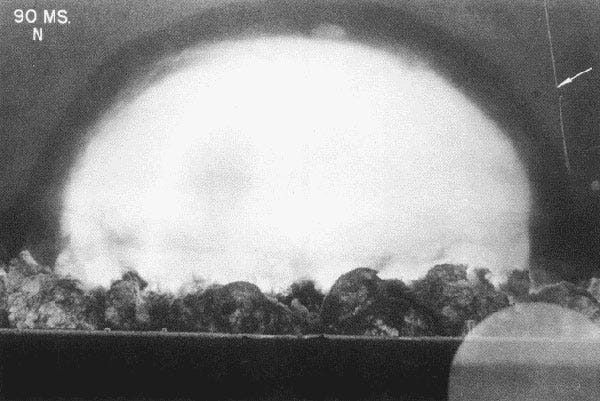

Nihon Hidankyo (in English it translates to something like The Japan Sufferers Confederation, which is short for the Japan Confederation of Atomic and Hydrogen Bomb Sufferers Organizations) was established in 1956 after America’s Castle Bravo thermonuclear test on Bikini Atoll caused the crew of a Japanese fishing boat and the inhabitants of nearby atolls acute radiation sickness. The confederation’s ongoing fight in the nearly 70 years since to abolish nuclear weapons deserves our attention and support more than ever in this moment, when the threat of nuclear conflict is escalating, with two nuclear powers—Russia and Israel—embroiled in full-scale wars, others such as the US modernizing their nuclear arsenals, and restrictions on long-range missiles being abandoned in Europe and Asia. The poignant first-person accounts gathered, publicized, preserved, and passed on by Nihon Hidankyo have special value in our technocratic world, where the suffering of real breathing individuals is so often airbrushed into emotionally numbing statistics.

Although Nihon Hidankyo is never mentioned directly in On Oppenheimer, Hirano considers the perplexity of the hibakusha at the the historical Oppenheimer’s push to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki and at his lifelong refusal to express any remorse for the death and agony that resulted. Moreover, the essay culminates with some reflections on Akutagawa Prize winning hibakusha author Kyoko Hayashi’s novel Ritual of Death, which Nihon Hidankyo and its sister organization No More Hibakusha, has marked for preservation in a special library of hibakusha art and literature.

Nearly 80 years since atomic bombs were used in war and more than 30 years since the end of the nuclear standoff that was the Cold War, we are all too easily lulled into a false belief that the dormancy of nuclear weapons and their cataclysmic power is assured and forget that the need to abolish them is as imperative as ever. The exceptions to this complacency, perhaps, are when world events briefly push the danger into the forefront of our minds, such as when North Korea succeeded in launching solid fuel ICBMS that can reach North America or when Putin threatens to nuke Ukraine. Except during these fleeting moments in the news cycle, it takes a special effort to remember that the Damocles Sword of nuclear holocaust hangs over humankind constantly.

The capacity for nuclear weapons to wipe out or permanently stunt the potential of humankind puts it in the category of what Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom has dubbed existential risks. Other existential risks besides nuclear weapons include:

Pandemics (naturally occurring or genetically engineered)

Global warming

Self-replicating nanotechnology

Ecological collapse

Asteroid impacts

Global totalitarianism

Highly advanced machine learning1

The problem of securing our ongoing existence is the single most important moral and political issue because it is upon our existence that the possibility to even ask moral and political questions depends. Or to put it another way, it is only when we exist that the values that matter to us, including equality, freedom, justice, beauty, and the good, can even be thought. This might sound obvious, but it is a point that is too often lost amid the blind scramble to win concessions for our various pet causes.

Bostrom (along with the thoroughly repudiated longtermists and effective altruist cultists who constitute his most prominent followers) has defined existential risk so that the concept only applies to global technological humanity. In so doing, he has focused the conversation exclusively on preserving the potential of humankind to gain technological dominance over the natural world, systematically ignoring the worth of non-human existence. But as the conclusion to On Oppenheimer suggests, it is incumbent upon us to reject this moral lacuna. Although human existence certainly has a unique function insofar as humanity imbues our value to the universe, nuclear weapons and other existential risks should be conceived as an ever-present danger not just to homo sapiens but to our fellow organisms (and perhaps to future sentient AI) as well.

This point is powerfully evoked by a quote at the end of On Oppenheimer. It is taken from Hayashi’s essay From Trinity to Trinity, in which she recounts her visit, fifty years after her experience in the bombing of Nagasaki, to the Trinity Site in New Mexico where the first nuclear bomb test in history was conducted :

Until I stood on Trinity Site, I had thought that the first victims of nuclear damage on earth were us humans. I was wrong. There were others before us. They were here, without being able to weep or cry out.

It is my firm belief, for reasons I hope to write about elsewhere, that the empathy, ingenuity, and foresight we will require to protect the dignified existence of non-human beings is precisely what our species will need to survive in the coming decades and, with any luck, to sustain its own meaningful existence across spans of deep time.

Despite the constant news patter in recent years about global warming, the demands and distractions of daily life too often prevent us from seeing that the project of human civilization and the condition of the biosphere that enables it will collapse unless we all make sincere efforts to preserve them. Essays like On Oppenheimer and the awarding of the Nobel Peace Price to Nihon Hidankyo are opportunities to reflect on oft ignored threats to our shared future and on our duty to overcome them.

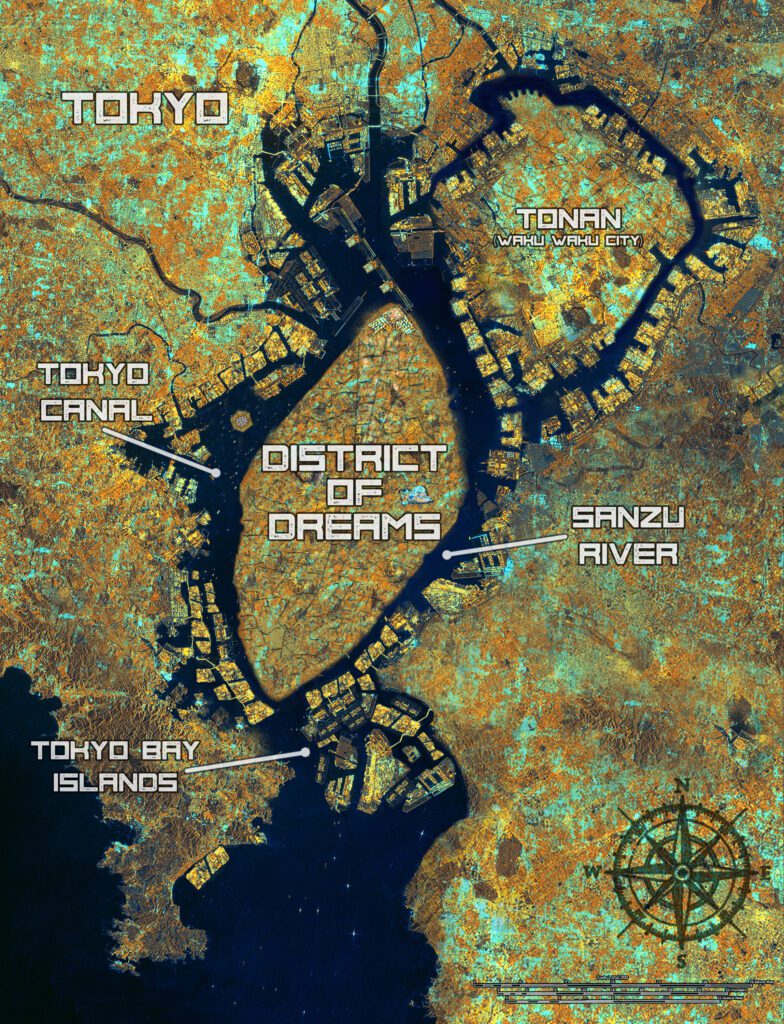

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle trilogy (Skyhorse Publishing), a science fiction trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo. He also translates Japanese literature, including the bestselling novel A Man (Crossing) by Keiichiro Hirano, and serves as a writing consultant for a well-known Japanese video game company. His translations, essays, and short stories have appeared in such publications as Granta, The Southern Review, Monkey, and The Malahat Review.

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle trilogy (Skyhorse Publishing), a science fiction trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo. He also translates Japanese literature, including the bestselling novel A Man (Crossing) by Keiichiro Hirano, and serves as a writing consultant for a well-known Japanese video game company. His translations, essays, and short stories have appeared in such publications as Granta, The Southern Review, Monkey, and The Malahat Review.

More about Eli here.

Follow him on BlueSKy: @elikpwilliam

Or for more essays like this, JOIN ELI’S NEWSLETTER

ALMOST REAL

essays on futurism, philosophy,

speculative fiction, and Japan

by Eli K.P. William