Humans in Literary Translation (HILT)

Creative people of all stripes—from writers to sculptors—often benefit from comradery and community with others who practice their art. This is no less true of literary translators.

Until the pandemic struck, I met regularly with a translator’s collective focused on Japanese fiction. It consisted of four members: Alison Watts, Louise Heal Kawai, Matt Treyvaud, and myself. We called ourselves Humans in Literary Translation—or HILT for short.

I have always liked the double meaning of the word “in” here. The preposition suggests both that we are working in the field of translation and that we ourselves have been translated. This latter nuance resonates with my belief that multilingual people translate not only their thoughts but also their identities when switching between languages.

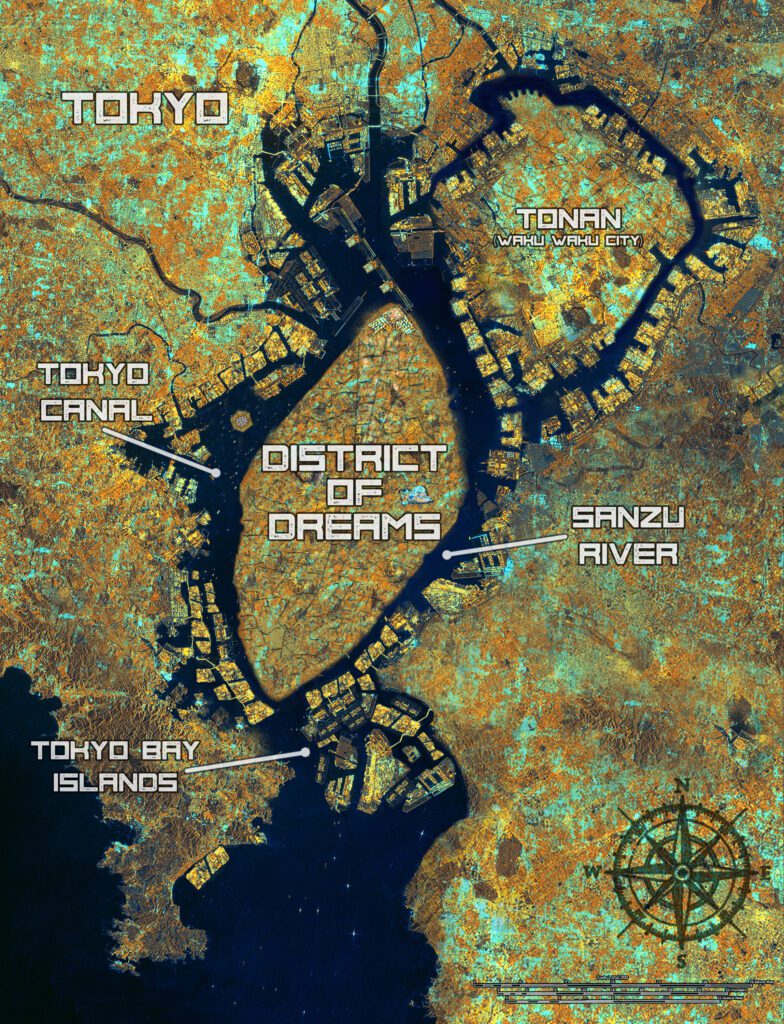

The origins of HILT date to a 2017 translation symposium held in Tokyo’s Jinbocho area, the heart of Japan’s publishing industry. The symposium boasted presentations on the topic of literary translation from top editors, agents, authors, and translators. In attendance were just about every semi-pro and aspiring literary translator from across Japan and beyond.

One of the presentations was delivered by translator trio, Allison Markin Powell, Lucy North, and Ginny Tapley Takemori. The topic was their translator collective, which they had dubbed Strong Women, Soft Power. By holding workshops and offering each other support, they had succeeded as female translators in a male-dominated industry.

Near the end of the symposium, I was standing around with my friend Alison Watts, chatting about everything we’d learned that day, and at one point one of us was like, “you know that translator collective thing, we could totally do that.” So I called over another translator in attendance, Matt Treyvaud, with whom I had co-translated the sci-fi novel Orbital Cloud by Taiyo Fujii, and Alison called over Louise Kawai-Heal, who both she and I knew from British Centre for Literary Translation masterclasses. Right then and there, we agreed to form a collective, and spent the next few months trying to figure out what the heck that meant.

The main purpose of our association was to hold workshops of our translations. These functioned much like creative writing workshops except that we sought feedback on stories we had translated from Japanese into English rather than stories we had written ourselves. Based on a suggestion made during the Strong Woman, Soft Power presentation, we decided on a format where each of us read our translation-in-progress aloud while the other three members marked up printed copies.

After the critique phase had concluded, we usually allotted thirty minutes to an hour to discuss the business of publishing and the problems we faced in the industry, nurturing each other with professional advice. Sometimes these conversations functioned like therapy sessions, in which the group mind played Freud to our publishing industry traumas and fixations.

Initially, we met in a conference room kindly offered by the Nippon Foundation, but over the years we gradually ran the gamut of Tokyo’s many rental meeting spaces. Our sessions often ended at yakitori restaurants (never another kind of food, who knows why).

One of our final in-person meetings was at the home office of publisher Bungei Shunju, in a room directly beside the solitary confinement chamber for novelists who have missed their deadline… (As a novelist who has missed more than one deadline myself, I certainly didn’t envy the poor procrastinators who had ended up in there.)

All of us benefited in different ways from our modest association, whether by honing our translation chops, demystifying the business of publishing, or simply gaining confidence. In my case, I garnered all of the above and so much more. In particular, membership in HILT led directly to publication of my first full novel translation as I described in a post on the Southern Review blog.

I still consider myself a member of HILT in spirit. Sadly, we are not as active as we once were. Our momentum began to slow when I realized that I want to dedicate my creative energies in the coming decades to writing rather than translation. Then covid hit, forcing our already fizzling workshops into a less-intimate virtual format (and putting an end to the halcyon days of yakitori…) At time of writing, the four of us have not been in a room together for almost three years.

The idea of an exclusive artist’s collective might sound to those on the outside like some kind of cabal or conspiracy. But for us it was never about plotting or competition. We gathered to offer mutual support and to work towards promoting Japanese literature and the translation industry as a whole so that everyone might benefit, readers, translators, and publishing professionals alike.

Our small community was a raft in a sea of creative and interpersonal challenges. I am grateful to have had the chance to be aboard.

blog post by Eli K.P. William.

blog post by Eli K.P. William.

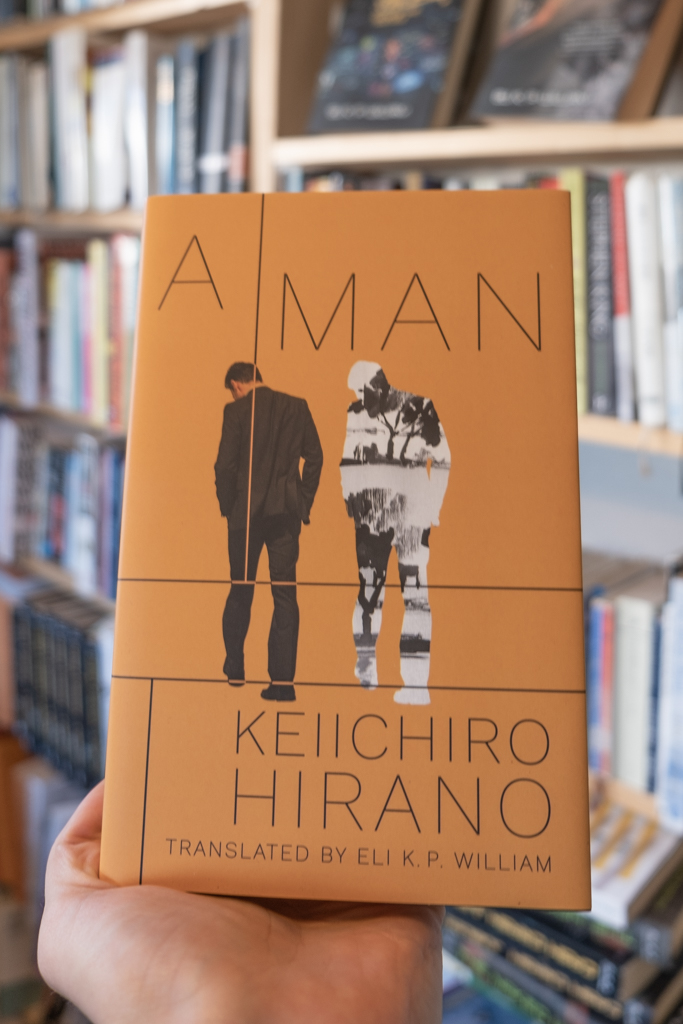

I am the author of three dystopian sci-fi novels: Cash Crash Jubilee, The Naked World, and A Diamond Dream. I also translate Japanese literature, including the bestselling novel A Man, by Keiichiro Hirano.

More about me here.

My Twitter: @Dice_Carver