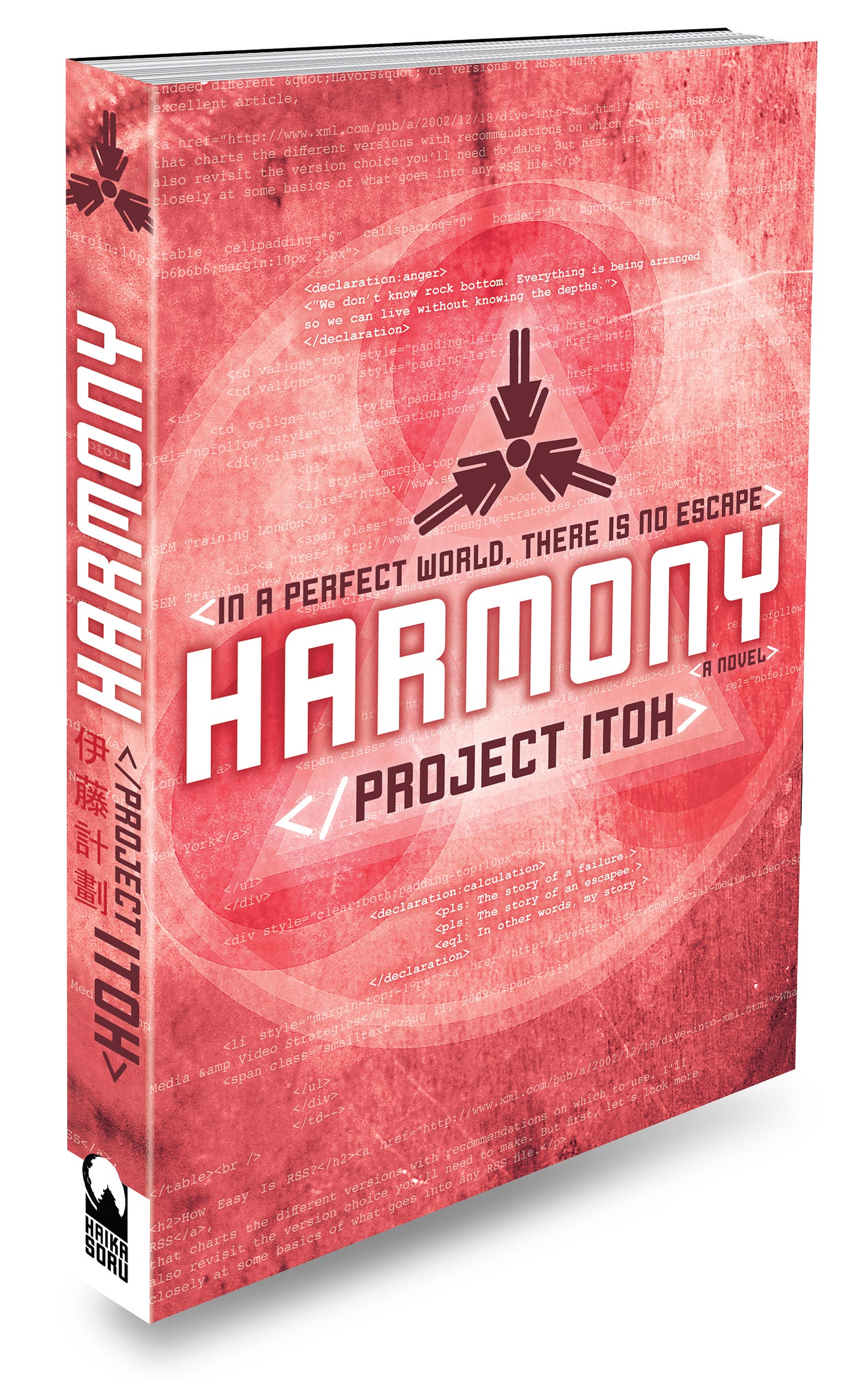

In the late 2000s, a young author with the unconventional pen name Project Itoh (伊藤計劃) appeared in the Japanese science fiction world like a bolt from the blue. His first novel Genocidal Organ (2007) was rated by a poll in Hayakawa Publishing’s annual SF guidebook (SFが読みたい) as the best novel in the genre from that decade, and his second novel Harmony (2008) received both of Japan’s most prestigious SF awards, the Seiun and the SF Grand Prix, as well as a special citation from America’s Phillip K. Dick Award.

Sadly, though Itoh’s influence and reputation persist to this day, his tenure as a professional author was all too brief. The tragic irony of Harmony—a near future tale about an oppressive global medical regime—is that Itoh edited the proofs while in and out of hospital during the final months of his long battle with cancer. Itoh died in 2009 at the age of 34, just two years after his novelistic debut.

Because Itoh himself passed away long before COVID-19 reared it’s spike protein head, we can only speculate as to how he would have reacted to the pandemic and its restrictions on freedom in the name of saving lives. His novels display respect for science and acceptance of a materialist metaphysics, so there is little reason to believe that he would have opposed fact-based public health recommendations such as vaccination, masking, and distancing on principle.

Still, when Harmony is read now, in the post-pandemic age, one can’t help noticing its relevance to the conflict—illustrated most vividly in the USA but played out around the globe—between those who opposed government measures to limit the spread of covid and those who willingly—sometimes eagerly—cooperated. Which side of the disagreement the novel falls on depends on whether you believe that the future it depicts is meant to be terrifying or desirable.

Although Harmony appears on first glance to be a work of dystopian literature targeted at a kind of medical authoritarianism, there are compelling reasons, as we will see, to treat it as a utopian tale that promotes government interventions to protect human life.

Lifeist Hegemony Through Physiological Surveillance

In a near future, the world has been taken over by the “ademedistration”, a global network of medical conclaves that regulate all social interaction. Through “WatchMe”, a system of countless nanobots called “medicules” that permeate the body, the homeostasis of every citizen is constantly monitored. Here we have a surveillance regime akin to the Big Brother panopticon of George Orwell’s 1984, except instead of utilizing television-like viewscreens to watch and listen in on the people, the surveillance infrastructure is embodied and dedicated only to the task of medical nannying.

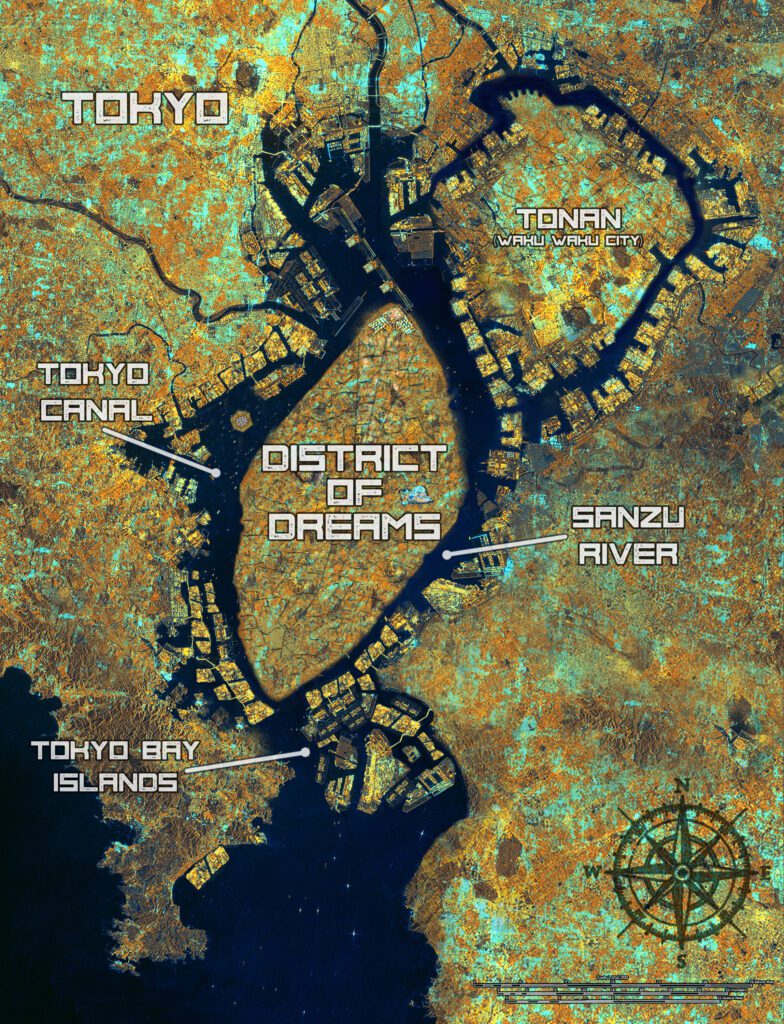

Driving admedistration institutions is “lifeism”, an ideology that treats the body as a public resource that must be kept healthy and forced to procreate. Procreation is a crucial biological service in the wake of a nuclear war called the Maelstrom that caused widespread genetic mutation, infertility, and depopulation. (Some passages suggest that the Maelstrom resulted from the events of Genocidal Organ, placing Harmony second in the same fictional continuum.)

For reasons we don’t learn until the epilogue, Harmony is told in Emotion-in-Text Markup Language (ETML). That is, every beat of the story is marked with representative emotions, mental actions, or moods, in a play on HTML. For example, the beginning of the English edition (translated by my friend Alex. O Smith) reads as follows:

I have a story to tell.

<declaration:calculation>

<pls: The Story of a Failure>

<pls: The Story of a Defector>

<eql: In other words, me.>

</declaration>

This formal experiment no doubt derives from Itoh’s original career in web design, through which he would have been familiar with front end code.

Our first-person protagonist is Tuan. In childhood, Tuan was friends with two girls, Cian and their leader Miach. Under the influence of Miach, who rails constantly against lifeism, the trio decide to plot an act of rebellion. But since the admedistration lacks any central authority, there is no clear target to strike. So Miach concludes that their only hope of resistance is to flout the moratorium on death by committing group suicide.

The girls then make a pact to take drugs that prevent absorption of nutrients from food, a kind of pharmaceutically-induced starvation that is supposed to go undetected by admedistration officials because the girls are still minors and have yet to receive WatchMe. When Cian tattles, she and Tuan are saved before it’s too late but Miach dies as planned. This leaves the two survivors to grow up without their leader, struggling to understand the meaning of Miach’s fatal dissent and their own failure to join her.

As an adult, Tuan finds employment with Helix, a militarized arm of the World Health Organization that fights for lifeism in developing regions around the world. Tuan has chosen a career in soldiering because it allows her to visit far-flung war zones where she can get her hands on cigarettes, booze, and narcotics. By hacking her WatchMe, she is able to to send spoofed physiological data, thereby quietly thumbing her nose at the health-enforcing authorities.

Tuan’s life of insalubrious impudence continues until she returns to Japan and reunites with Cian, who has taken a typical admedistration job and seems to have conformed to lifeist society. Then, over dinner at a nice restaurant, Cian kills herself in a gory display by cutting her own jugular vein.

Tuan soon learns that Cian’s death was part of a simultaneous mass suicide. Now, through admedistration propaganda news networks, the organizers of this mysterious atrocity demand that everyone murder at least one other person or they too will be forced to commit suicide.

The ultimatum seems uncannily reminiscent to Tuan of Miach’s morbid plotting when they were children, and she wants to understand how the bloodbath was perpetrated. Her investigations take her to Baghdad, now a locus of cutting-edge medical research, where she meets her father, the inventor of the WatchMe system, and later to the caves of the Caucasus mountains, where she confronts the villain behind a scheme to snuff out essential facets of human nature and inaugurate a kind of totalizing harmony.

Antivaxxer Dystopia or Science Credulous Utopia?

Contrary to what the high praise both within and without Japan might suggest, Harmony is not an exemplar of top-class story-craft. The characters, with the exception perhaps of Thanatos-channeling Miach, are two-dimensional at best. The dearth of description makes a missed opportunity of the exotic settings, and, combined with the comparatively plentiful dialogue, reduces most of the novel to a series of disembodied voices waxing intellectual. Even the philosophical discussions of consciousness and free will crucial to the denouement fail to stand up to the most rudimentary scrutiny. One must suppose that Itoh, writing on his deathbed, struggled to flesh out the vision of his final work as fully as he had demonstrated himself capable of in earlier stories such as Genocidal Organ.

Still, Harmony does represent a rare* and memorable example of a Japanese novel that fits in either the dystopian or utopian tradition—perhaps both at once. Like Ursula K. le Guin’s masterpiece The Dispossessed, which bears the subtitle “An Ambiguous Utopia,” Harmony constructs a nuanced future. Ultimately, the position it encourages readers to take on the medical nanny state remains inconclusive, making the text an interesting lens through which to consider the polarization around government responses to the pandemic.

If Harmony is classified as a work of dystopian literature as is standard**, it presents just the sort of dark future one might imagine the anti-vaxxer or the anti-masker to conceive. Harmony could then be read as a cautionary tale, illustrating the dangers of allowing the CDC or a similar medical body to tell us what to do. (Remember that the WHO is literally a global military force!)

However, Itoh’s future lacks many features that would make for a persuasive dystopia. For example, there are too many holes in the WatchMe system, with minors and touring soldiers outside its reach, for life under the admedistration to feel particularly suffocating or oppressive. A dystopia that is easy to escape hardly seems dystopian at all.

It may be that Itoh intended for readers to accept Miach’s insistence on the dehumanizing effect of legally mandating good health, but the novel contains scarce examples to back up her vituperations. Surveillance of our very cells would certainly be a terrifying prospect, while the homogenization of physical appearance that afflicts admedistration citizens presents an eerie image of obedience, as if to assert that following medical advice transforms human beings into interchangeable ants or zombies.

But as a response to a catastrophe like the Malestrom, formulating policy that is to some degree overbearing seems entirely reasonable. Indeed, there are worse things than being cajoled into taking care of your body when the survival of the human species is on the line. Would the morally appropriate response be to instead prioritize individual choice and condemn humanity to extinction?

Moreover, the admedistration mechanisms for encouraging compliance with lifeism seem mild, generally coming in the form of education and social pressure rather than force. Compare this to the lockdowns of 2020-2022 in countries such as Australia and China that were positively draconian even though the crisis they sought to mitigate (i.e. the pandemic) was far less threatening than worldwide nuclear fallout.

For people who are eager to obey public health recommendations in the name of longevity for all, I hazard that a fully functioning lifeist civilization would be a utopia. There, in the capable hands of admedistration scientists, with the most advanced medical technology the world has ever seen, we would all extend not just our lifespans but our healthspans and live without fear of two of the greatest woes human beings face—illness and death. Whatever we might lose in exchange, for some it would seem worth the sacrifice…

Whether taken as a dystopia, a utopia, or something else, Harmony anticipated many of the debates of the pandemic more than a decade before the word COVID-19 was even coined. When considering the highly politicized fight between libertarian extremists and virtue signalling rule-followers around whether governments should mandate masks, lockdowns, and vaccines, there has been a tendency for empirically minded liberals and progressives to dismiss the skeptics as far-right or irrational imbeciles. But Itoh reveals the core of meaningful objection on the other side—the dangers of the medical nanny state taken too far—while simultaneously describing an extreme scenario in which curtailments of freedom may be justifiable.

Itoh was clearly a perceptive writer. If only he had lived to see how our past matched up to his future…

Notes

*Japanese proto science fiction of the late 19th and early 20th century shows a preoccupation with political dystopias and utopias. However, examples are much harder to find in the later Japanese tradition than that of the Anglophone.

**In her article on the history of manga and anime, Ada Palmer classifies Harmony as a “quasi-utopia.”

I am the author of three dystopian sci-fi novels: Cash Crash Jubilee, The Naked World, and A Diamond Dream. I also translate Japanese literature, including the bestselling novel A Man, by Keiichiro Hirano.

More about me here.

Follow me on Twitter: @Dice_Carver

Or if you want more essays like this one, JOIN MY NEWSLETTER.