Book Review: Binge

Foray Into Flash Fiction by Douglas Coupland of Generation X Fame

Canadian author, designer, and visual artist Douglas Coupland is best known internationally for his 1991 debut novel, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. Although Coupland is not a Gen X-er himself but a Boomer, the novel has frequently been praised for adroitly capturing the spirit and voice of its titular generation when it was youthful and coming into its own. Now in his sixties, Coupland is an Officer of the Order of Canada (essentially the nation’s equivalent of being knighted). He has published thirteen novels, several short story collections, and numerous books of non-fiction.

Although his fiction does not generally qualify as science fiction per se, as his stories are almost invariably set in the present day rather than the future or alternate worlds, he is one of those postmodern authors, like J.G. Ballard in his urban disaster trilogy, Don Delillo in Cosmopolis, or Richard Powers in Plowing the Dark, who presciently explore the impact of technological development on sub-cultures grappling with the absurdity of life under capitalism. His 1995 novel, Microserfs, for example, was a ground-breaking and perceptive depiction of Silicon Valley tech culture years before anyone even imagined the dotcom bubble.

Coupland’s literary output kept pace with the changing times until release of his 2013 novel Worst. Person. Ever. This would be his final book of fiction in the 2010s, leaving us without the stories of an insightful cultural commentator to help ground us in an age of ever more frenetic social disruption.

In Binge (2021), his first book of fiction in nearly a decade, Coupland resumes his engagement with technological and cultural currents of the now. According to the author in an interview with Steve Paikin, the title, Binge, refers to the mode of media consumption that defines our era. We typically associate bingeing with the streaming of entire television seasons or series over the course of just days or even hours. But Coupland claims to have modelled Binge on the discussion boards of the website Reddit to which he ascribes a compulsively readable quality. His hope is that the book will likewise spur its immediate and uninterrupted reading.

Crammed into 250 pages are sixty narrative works. These consist mainly of anecdotes, vignettes, and character portraits; few are full‐fledged stories, a point Coupland himself seems to acknowledge implicitly: “I realize this isn’t even an actual story, with a beginning and end,” admits Erik, the overweight, gay, sexually unfulfilled narrator of “Norovirus,” the final piece in the collection.

Each of the five-dozen works has been given a punchy title of no more than three words such as “Thong,” “Theme Park,” and “Resting Bitch Face.” Although there are recurring characters (notably Trashe Blanche, Erik’s moniker when in drag), recurring incidents (a young man’s assault with tiki torches on his molesting football coach), and recurring images (bodies stashed in car‐top cargo bins), the book does not have a traditional plot. A better analogy for the collection than streaming television or online forums might be the strobe of disconnected moments found on video sharing platform TikTok.

A heterosexual incel on a plane receives advice from Trashe Blanche on how to get laid. A young woman with the rare blood type RHnull is cradle‐robbed by a man who secretly gets rich off selling her and their daughter’s samples to researchers. An ex‐globetrotter searches for the unknown neighbour who keeps anonymously printing hardcore pornographic images on his wireless printer only to be abducted by him.

With a different first‐person perspective for each work, we are treated to a panoply of narrative tasters. Indeed, the book could have been called Appetizers or Flights, and we might question whether its flash‐fiction morsels of some four pages offer portions substantial enough to be binged.

The collection, abundant as it is with viewpoints, would seem to demand a unique voice for each character. Instead, Coupland’s highly distinctive writing style, which usually brings a welcome stamp of consistency to the sustained plots of his full‐length novels, tends to overpower the prose and narration across these more fleeting and variegated works. Often it is difficult to identify the gender, age, or outlook of a protagonist until the story is almost over.

This could be an intentional strategy to meld perspectives and thereby emphasize our underlying sameness, perhaps along the lines of Charlie Kaufman’s stop motion animated film Anomalisa, in which everyone on Earth is revealed to be a single person. But it seems more likely that in the pursuit of that bingeable quality suggested by the title, Coupland has intentionally sacrificed diversity of expression for stylistic consistency more conducive to smooth reading.

Often the stories carry a moral, echoing themes Coupland explored in his 2016 essay and fiction compendium, Bit Rot. For example, his contention that psychiatric pharmaceuticals are a boon to society is illustrated in “Adderall” by a hoarder who finally starts tidying up her junkyard of a house after a visitor gives her prescription amphetamines. His lamentations about how the internet has permanently transformed our brains is revisited in the introductory story “Alexa,” in which the photographic‐memory‐endowed narrator notes that people tend to retain less information since the advent of search engines.

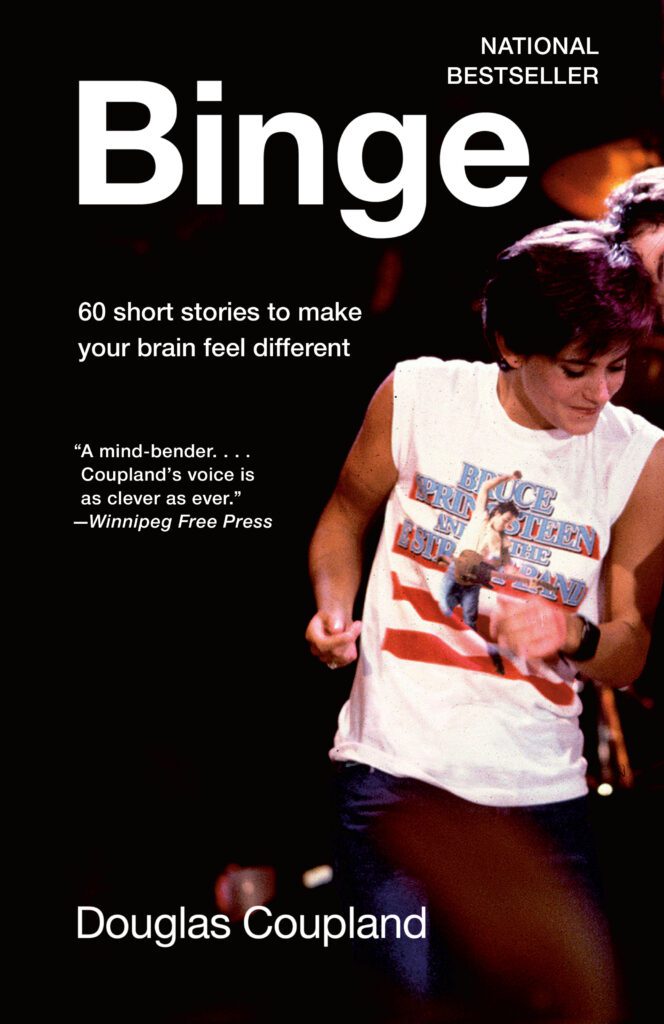

The Literary Review of Canada praised Binge for its “up-to-the-minute language,” listing several acronyms in common currency, including yolo, nsfw, and fomo. Coupland has always had an ear for fresh lingo and has dabbled in internet slang at least since his 1995 Microserfs. But Gen Zers and Millennials may by struck by the incongruously outdated pop‐culture references. The vast majority—Carry, Alanis Morrisette, Monty Python, Archie, Princess Mononoke—date from between the 60s and 90s, and almost none (I could find only Childish Gambino) from the 2010s. The cover of the book (see above), a blurry, analogue still of Courtney Cox in the music video for Dancing in the Dark with Bruce Springsteen awkwardly clipped from the frame, screams 1980s, as if to warn prospective readers of the anachronisms inside.

We might be tempted to chalk up his lapse in capturing crucial elements of the zeitgeist that has been his stock‐in‐trade to a lack of familiarity with the cultural touchpoints of recent decades. But we should also acknowledge that widely resonant references are increasingly hard to come by now that the internet has shattered the traditional monoliths of television, cinema, radio, and print. Perhaps Coupland can be forgiven for digging up famous artifacts from the halcyon days of universal entertainment in an age where algorithms have buried each of us in isolated heaps of shiny, new information trinkets.

However we choose to understand the book’s odd nostalgic quality and its one‐size‐fits‐all voice, Binge delivers on the promise of its subtitle, “to make your brain feel different,” offering insights and illuminations about existence in the twenty‐first century, all punctuated by Coupland’s trademark wordplay and wit.

When is he going to give us another novel?

*This essay was adapted from a review that originally appeared in the winter 2022 edition of The Malahat Review.

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle trilogy (Skyhorse Publishing), a science fiction trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo. He also translates Japanese literature, including the bestselling novel A Man (Crossing) by Keiichiro Hirano. His translations, essays, and short stories have appeared in such publications as Granta, The Southern Review, Monkey, and The Malahat Review.

Eli K.P. William is the author of The Jubilee Cycle trilogy (Skyhorse Publishing), a science fiction trilogy set in a dystopian future Tokyo. He also translates Japanese literature, including the bestselling novel A Man (Crossing) by Keiichiro Hirano. His translations, essays, and short stories have appeared in such publications as Granta, The Southern Review, Monkey, and The Malahat Review.

More about Eli here.

Follow him on X: @Dice_Carver

Or for more essays like this, JOIN ELI’S NEWSLETTER

ALMOST REAL

essays on futurism, philosophy,

speculative fiction, and Japan

by Eli K.P. William